As I have now had the time to sufficiently “decompress” from the fall semester, a little reflection is in order. This was my first semester as a graduate student at Catholic in the Greek and Latin department. It was a busy, and often stressful, semester, but (Deo Gloria!) I did well. I’m pleased with how the semester went, even if I could have done better (in Syriac especially).

I took four classes: a Greek course in which we read Homer, Latin Prose Composition, a Late Antique History Seminar, and Intro to Syriac. Reading Homer was difficult early in the semester. I had not read much Greek poetry before that, and I’ve still not read much Odyssey and Iliad in translation. The difficulty, as many will tell you, is the vocabulary. However, by the middle of the semester, I was reading along without too much difficulty. For my term paper, I wrote on the use of Homer by Gregory of Nazianzus in a few of his dogmatic poems. This was a lot of fun to write, and if possible I’ll adapt some of my paper into blog posts.

Latin Prose Composition was a terrific course, though quite difficult. We used the venerable textbook by Bradley and Arnold (something with which my fellow classicists can no doubt identify). As I’ve never had a formal course in Latin Grammar before (I was mostly self-taught before arriving at Catholic), I learned quite a bit. We regularly translated English into Latin, which was beneficial and challenging. In addition to now having declensions and conjugations drilled into my head, I have a much better grasp of syntax. Soon I’ll get to apply all this to reading Cicero, which will be lots of fun!

The Late Antiquity seminar was quite useful. The literature is so vast that it was more an introduction to the resources than anything else, but I read some useful books, both primary and secondary. For my term paper, I wrote on Origen and Greek philosophy in the third century. The paper was historical in its focus: I argued that “philosopher” is the most appropriate title for Origen, and that to understand the man one must understand how Greek philosophy operated during his life. The paper was more of a survey than anything else, but I may expand some of the ideas into further papers (Deo temporeque volentibus!).

Intro to Syriac was, at the end of the semester, my most difficult class. I did well early on, when I had more time, and when the material was a bit easier. But by the time we got to all the weak verbs in the final weeks of the semester I had a hard time keeping up. This was my first semitic language, so much was new to me. I’m thankful the formal grammar instruction is over: now we’ll move on to reading texts, which is the fun part!

The semester had several other milestones. I finally completed the Ancient Citations Index for volume 2 of the Cambridge Companion to Ancient Mediterranean Religions. Prof. William Adler, one of my undergraduate professors, edited this volume, and it contains two articles by Catholic faculty (Fr. Sidney Griffiths and Prof. William Klingshirn). It’s due out next year.

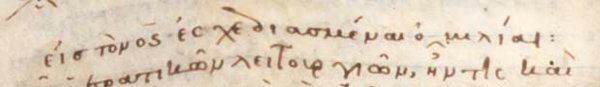

I also presented my first academic paper at the annual meeting of the Byzantine Studies Association of North America. The paper dealt with digital stemmatology and the Palaea Historica, a text on which I worked with Prof. Adler at NC State. I enjoyed seeing Boston: the city is a lovely place. My paper was well received, and I was able to hear interesting talks from others.

I thankful for how well the semester went, and most especially because my wife and I are no longer in a long-distance relationship. She finished her bachelor’s degree this fall at NC State University, graduating summa cum laude and valedictorian with a degree in Computer Engineering! I am extremely proud, and enormously thankful to have her as my wife. As smart as she is, she is even more loving and loyal. She will now be joining me in DC and starting her job in January.

Τῷ δὲ δυναμένῳ ὑπὲρ πάντα ποιῆσαι ὑπερεκπερισσοῦ ὧν αἰτούμεθα ἢ νοοῦμεν κατὰ τὴν δύναμιν τὴν ἐνεργουμένην ἐν ἡμῖν, αὐτῷ ἡ δόξα ἐν τῇ ἐκκλησίᾳ καὶ ἐν Χριστῷ Ἰησοῦ εἰς πάσας τὰς γενεὰς τοῦ αἰῶνος τῶν αἰώνων, ἀμήν. (Eph. 3:20)

ἐν αὐτῷ,

ΜΑΘΠ